WASHINGTON — Scientists studying Jupiter's weather for nearly 40 years made some unexpected and slightly mysterious discoveries about how temperatures in the planet's different belts and zones fluctuate.

The researchers tracked temperatures in Jupiter's upper troposphere, the layer of the atmosphere where its signature striped clouds form and where the planet's weather occurs.

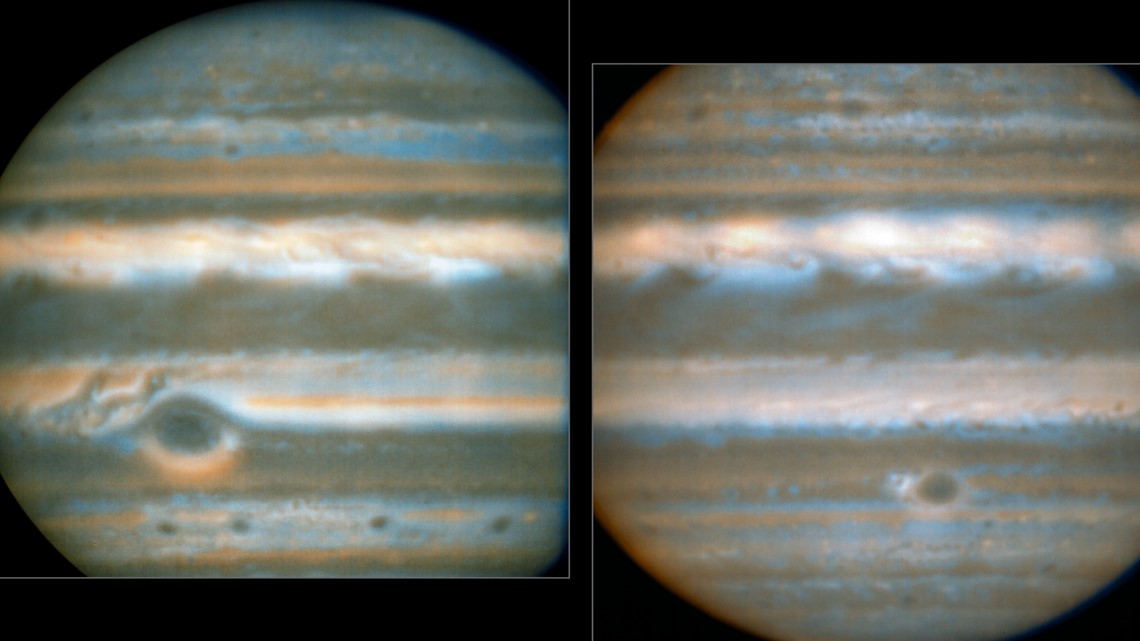

Astronomers have known since NASA's Pioneer 10 and 11 missions of the 1970s that generally, Jupiter's whiter, lighter-colored bands – known as zones – are associated with colder temperatures. Its belts – the darker, brown-red bands – have warmer temperatures.

But without long-term data, scientists couldn't track how temperatures and weather patterns changed over time.

For the new research, published Monday in Nature Astronomy, scientists studied images of the bright infrared glow above warmer regions of Jupiter's atmosphere. Scientists collected images at regular intervals over three of Jupiter's orbits, each of which lasts 12 Earth years.

What they discovered was surprising: Scientists found Jupiter's temperatures rise and fall following definite periods that aren't tied to the seasons – or any other cycle scientists know about. Because Jupiter's axis tilt is only 3 degrees, compared to Earth's 23.5, it has "weak seasons," according to NASA, and the researchers did not expect to find temperatures varying at regular intervals.

Researchers also found a connection between temperature shifts in regions thousands of miles apart. According to NASA, temperatures acted like a mirror image across the equator. As temperatures went up at specific latitudes in the northern hemisphere, they went down at the same latitudes in the southern hemisphere.

“It’s similar to a phenomenon we see on Earth, where weather and climate patterns in one region can have a noticeable influence on weather elsewhere, with the patterns of variability seemingly ‘teleconnected’ across vast distances through the atmosphere," said Glenn Orton, senior research scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and lead author of the study.

“We’ve solved one part of the puzzle now,” said co-author Leigh Fletcher of the University of Leicester in England.

Orton and his colleagues began this work in 1978, fighting to win observation time at major telescopes around the world, then combining years' worth of observations from different telescopes and instruments and poring through that data to search for patterns.

The study lasted so long, none of the students assisting with research when it was completed had been born when the study began.

Scientists hope the findings help them on their quest to predict the weather on Jupiter, which could contribute to climate modeling for giant planets across our solar system.

“Measuring these temperature changes and periods over time is a step toward ultimately having a full-on Jupiter weather forecast, if we can connect cause and effect in Jupiter’s atmosphere,” Fletcher said. “And the even bigger-picture question is if we can someday extend this to other giant planets to see if similar patterns show up.”